Pensacola Magazine | Cover story | 2022 | print and digital

by Kelly Oden • photos by Guy Stevens

While Pensacola has always been home to a robust art community, in recent years the diversity and scale of the art being produced locally has grown by leaps and bounds. Perhaps that is a a reflection of the community support and nurturing given to the arts in Pensacola. After all, without viewers, collectors, patrons and appreciators, such an abundance of creativity could not flourish. This month, we are doing our part to highlight some of the interesting artists, exhibits and events that have popped up on our radar. Whether you are interested in large scale murals, outsider art, public art, film or eco-friendly clay firing, you’ll find something to admire in this special Art Watch edition of Pensacola Magazine.

Daniela de Castro Sucre

While you may not recognize Daniela de Castro Sucre’s name, you are sure to have seen her bold murals on a variety of buildings around Pensacola. From the vibrant hummingbirds at Garden and Grain and the translucent ghost crabs on Pensacola Beach to the large-scale hands at First City Art Center, de Castro Sucre’s work seems to be everywhere— and that’s a wonderful thing for Pensacola.

Born and raised in Caracas, Venezuela, de Castro Sucre’s work is often informed by the culture and beauty of her native country. “Growing up in Venezuela was really wonderful,” she said. “Our culture is very family oriented, and I have a big family. So, that is very much my memory of it. And the culture is also so focused on nature. The nature scene in Venezuela is insane—it’s so beautiful. It’s incredible. My mom would always find me outside looking at leaves when I was kid. So, I grew up with this appreciation for nature.”

Sucre and her family fled the brutal dictatorship in Venezuela in 2006 when de Castro Sucre was 15 years old. The hardships in Venezuela helped de Castro Sucre gain an appreciation for street art, a topic she discussed at length in her 2019 Ted Talk, The Power of Street Art. In her talk, she described art as a universal language through which people can understand and connect to each other. For de Castro Sucre, street art is a unique extension of that language, in that it has the ability to reach so many people and that its message can be both local and universal.

De Castro Sucre’s family settled in South Florida where she studied with Conchita Firgau, a renowned Spanish realism painter also from Venezuela. Firgau became her mentor and her inspiration as an artist.

“She was a really fantastic painter and I studied with her,” de Castro Sucre recalled. “It was more like a master apprenticeship kind of deal. It was kind of old fashioned. I studied with her for three years. It was Conchita who formalized art and painting as an option for me.”

After four years, de Castro Sucre’s visa expired and she traveled to Spain where she studied pharmacology and met her future husband, who grew up in Gulf Breeze. The two married and moved to Pensacola where Sucre studied graphic design at Pensacola State College. Sucre’s art career coalesced around two major wins. First, she won the poster contest for the Great Gulf Coast Art Festival in 2017. Next, she was chosen to paint the mural inside Perfect Plain Brewing Co., which depicts Rachael Jackson, wife of Andrew Jackson who described Pensacola as a “perfect plain.”

That mural has since been painted over, but de Castro Sucre doesn’t mind so much. “Andrew Jackson does have a complicated history,” she said. “So, given the volatility of everything, specifically in the middle of the Black Lives Matter protests, it is very understandable that the decision was made. And again, I do not see murals as eternal things. They change with time.”

Her love of nature has continued to inspire much of de Castro Sucre’s work, which often weaves natural elements and materials with bold colors and realism.

“I have a thing with tiny animals, tiny leaves, tiny everything,” she said. “Honestly, I’ve been like this since I was a kid. I realized later in life how everything ties in together. And even when I was studying science, my favorite thing was using a microscope to look at things really up close. There is this amazingness when you take a second to look at the details and the lights and the shadows of something. So that’s been a bit of a conceptual thread across many of my murals—to enlarge normal objects of everyday life and really see the detail up close. That was kind of what it was with the ghost crabs, which are native. I love to do a ton of research before every job and I learned that the ghost crabs change color over time and all these wonderful little things. Also, they’re in constant danger because their environment keeps shifting. So my work is very environmental as well. I’ve always liked ghost crabs. I have a thing for transparencies and they glow in the dark. I like to have fun with my work.”

In 2021, hands emerged as a thematic focus point in de Castro Sucre’s work, with murals involving hands developing at First City Art Center as well as in Miami and Venezuela.

“I have this fixation on hands,” she said. “I love drawing hands. I think they’re so expressive. I think that if you were unable to see people’s faces from now on, you would look at their hands to see what they mean. You know, it’s a language in itself. So, I have this focus on hands. It’s been a theme this past year especially. I’ve made three murals with giant hands. The concept behind the First City mural was the creative mind. The mental search for solutions and the creative ideas that you come up with. So, the mural is a bunch of hands stretching and pulling and playing. And then the main face you see is a kid behind the hands who is kind of holding something. It’s meant to represent the process of coming up with creative solutions.”

De Castro Sucre has been impressed with the level of support the Pensacola community has given her as an artist. She even started the Pensacola Muralists group in July of 2021 in order to connect with likeminded artists and to create a supportive community of muralists and street artists.

“I just wanted to create a network of muralists,” she explained. “We have great artists here and none of us knew each other. I’m really about friendly competition. There are going to be jobs that we all compete for, but it doesn’t have to be this concept that you have to keep your secrets to yourself in order to keep your edge. That mindset is falling apart now. There are so many mural artists especially but artists of all kinds who actually teach their work. They show their techniques. They teach new artists how to charge for example, and they just open up the doors. I think that makes the industry as a whole thrive. So there is that incentive. Then, there is the incentive to create a fun community of people that we’d like to hang out with. We have graffiti artists, street artists, airbrush artists and brush artists like myself. We also have ceramicists and studio artists, so it’s not just street art, but we all have a love for street art and

the knowledge of how positive it can be for our community. And then we do have some goals as a group. We would like to see more murals in some areas of Pensacola—the Tanyard district has been a topic for us because it is really close to downtown but it doesn’t have any of the zoning laws or the regulations that downtown has to protect historic buildings, so that’s understandable,” she said. “We want to change the codes, too. For example, the code on the beach doesn’t allow any murals, even though there are murals everywhere. In the future, if we were to become a nonprofit, we can apply for grants as well,” de Castro Sucre explained.

To view Daniela de Castro Sucre’s work, follow her on Instagram @danielapaints.

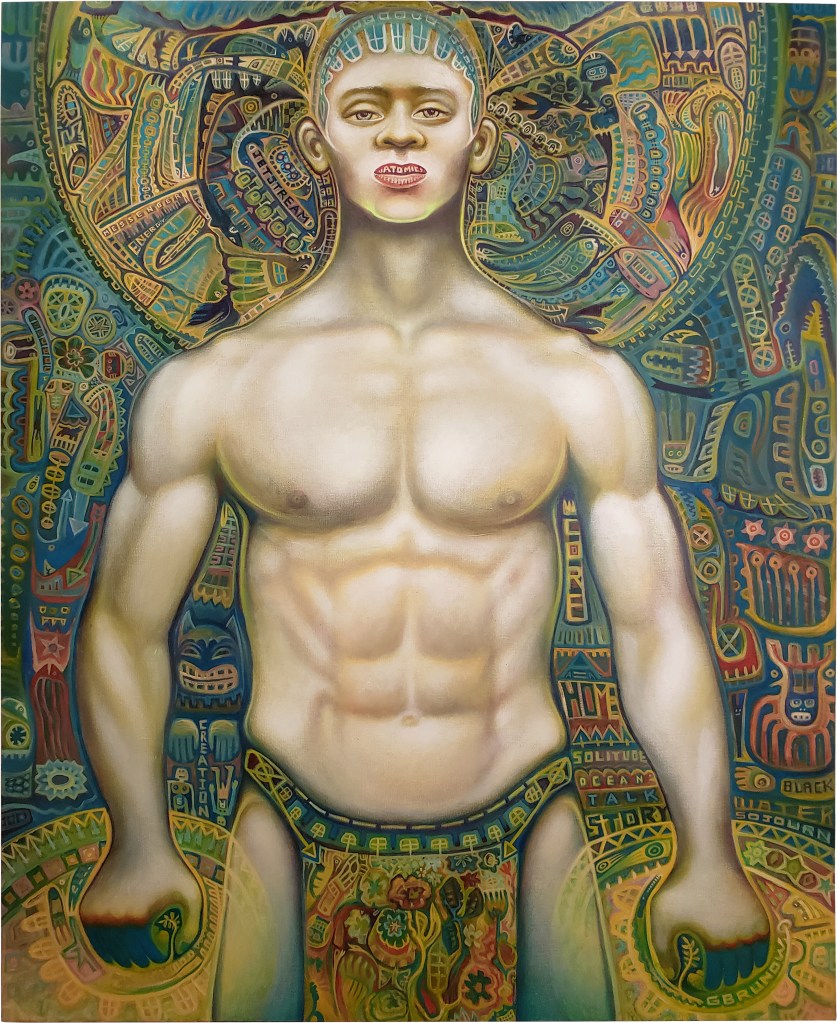

Géza Brunow

It’s hard to describe the style of art Geza Brunow creates because his body of work is both prolific and varied. Working in different mediums including casein, water-based pigments and oils, scratchboard and pen and ink. Brunow creates portals into lush inner worlds> From whimsical dreamscapes and surrealist mindscapes to metaphysical soulscapes and his most recent amorphous paintings, his work seems to harness both a sense of hi emotional terrain and the universal human experience as a whole.

Brunow sees himself as both a visual artist and a storyteller. His work is free-flowing but often informed by conversations, fleeting images and a narrative that emerges throughout the process. “I just like to hit a surface and attack,” he explained. “More often than not, I might not even have an idea. I’m just moving color around and all of a sudden, there’s the narrative. I’m working on two or three pieces right now and with one of them, I have no idea what the narrative is yet. Not at all. If I can finish it and find that narrative, it takes the work out of the decorative and into the actual storytelling.”

Brunow’s passion for painting is evident in his work ethic as well. He paints about 30 hours per week in stretches of eight to ten hours at a time. “Once I get started, I just can’t stop,” he said. “I’ve got the vision and the longer it goes, the better I get. By the tenth hour, when I’m just drained, I’m also in the pocket. I don’t want to stop, but I have to because I’m beat. But that’s when the magic really happens. I don’t know what it is. You’re in the flow. You’re in the art trance.”

Born in Germany to an American military father and a Yugoslavian mother, Brunow has lived and traveled “everywhere.” His formative years, however, were spent on the idyllic Whidbey Island in Puget Sound. “It was bliss because we were allowed to roam anywhere we wanted on that island and it’s a big island,” Brunow recalled. “There wasn’t any of this having to be careful or worry that a predator might ask you to get into the car with him. We had so many special spots on that island. There was this glade on a cliff overlooking the water and we used to meet there and play and nobody knew about it but us. I found a washed up killer whale once and I pulled a tooth out of its mouth. It was rotting and stinky, but I needed to have it. Those were some great years. They really informed me.”

Brunow started drawing as a kid and in high school, he created a portfolio to submit to a prestigious summer art school in Washington, D.C. Before he could submit it, the portfolio was stolen from the school. “It broke my heart,” he said. “It was years of drawings. It was a big portfolio. It kinda killed me. It killed my spirit. My art teacher gave me time to draw another one because the submission time wasn’t up yet. I hurriedly drew another one and that one was stolen, too.” The experience was so painful for Brunow that he swore off art for ten years.

Brunow attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison and earned a degree in journalism. After college, he was living in Minneapolis and working part-time at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. “I just sort of fell back in love with art,” he recalled. “I was seeing all these great artists come through the doors, like Chuck Close and all these French artists. We had some big names coming through and I just thought all of it was really good. I was reading all the Art Forum magazines during my breaks and I kind of went into it again through the backdoor.” Géza started helping out with faux finishes for exhibit sets, which eventually led him to form a successful faux painting company with a few friends.

At that point, it hadn’t occurred to Brunow that he could make a living as a fine artist. “I love America, but especially the United States, being an artist isn’t considered a real occupation,” he said. “Everywhere else you go they’re so welcoming to artists.” It was a trip to Italy that made him realize that he could have a career as a professional artist. “I was watching this woman paint the Ponte Vecchio on the River Arno in Florence. She was doing an impressionist piece. It was all sort of swirling and goopy. She really captured it.” The two began talking and Brunow learned that she made her living as an artist and he was blown away. “She was sort of the fin de siècle,” he said. “She clinched it for me. That was a turning point for me in terms of my art.”

Brunow later lived in New Orleans for ten years and the city’s love of art and culture served as a muse for his work. “New Orleans gave me respect,” he explained. “New Orleans respected me as an artist, which was really novel. New Orleans loves culture. They love the arts. But in other parts of the country, a lot of people look down on you if you’re a creative individual unless you’re famous. New Orleans was the first place that really made me feel like I was home.”

Inspired by his time in New Orleans, Brunow created a book of ink drawings titled, How to Draw A Werewolf. ”I started working with these really fine nibbed pens and I started doing these doodles of this guy named King Foraday,” Brunow explained. “Mostly things aren’t going great for him, but every once in a while he’s king for a day. Because that’s what it felt like in New Orleans—today I’m king for a day, but most of the time, it’s kind of hard here. He’s sort of like a whimsical everyman, but also a part of that whole Cajun folklore of the loupgarou. I originally did the book as a gift for a collector who has been really good to me. And then I did all these other inks of this character. I got carried away and swept up with the good humor that this loup-garou has. Pratfall after pratfall, situation after situation, he kind of just keeps pressing on. That werewolf is also an idea I have of myself. There’s a part of me that’s wild and perhaps unpleasant. And then there’s a part of me that’s very fun-loving and wonderful and happy. So, when the full moon rises, it’s the loup-garou coming out. That’s where this guy came from. It was kind of a synthesis of the New Orleans experience.”

While Brunow loved the artistic climate of New Orleans, life in the Big Easy didn’t always live up to its nickname. “It was a struggle the whole time, too,” he said. “It wasn’t easy. I was having a lot of issues with noise and in New Orleans, you’re all on top of each other. Hurricane Katrina just compounded everything. I stayed for two years after Katrina and then I blew a gasket and I had to get out.”

After spending some time in Asheville, Brunow was looking for a change and a collector of his work suggested he check out Pensacola. Brunow was skeptical, but the surfer in him decided to give it a shot. “The minute I landed, I fell in love,” he said. “That’s the God’s honest truth. I thought, ‘This is it. It’s got 18 to 20 miles of dedicated beach path to bike on—how come nobody ever told me about this place?’ I’ve been to every beach in this country and this place is amazing. It’s the closest I’ve come to that feeling of freedom I had on Whidbey Island.”

With this newfound feeling of freedom, Brunow has been channeling the muses in his studio, churning out work that is more positive in theme. His most recent major work is titled Prometheus (Metamorphosis). The large-scale work is a casein painting on a 60-by-40-inch canvas. It features what Brunow calls an “archetypal everyman” that represents all races in one being. While the final piece is powerful and positive in message, Brunow said it didn’t start out that way. “I was doing a self portrait,” Brunow explained. “I was gonna do this tattooed guy and all of his tattoos were of all the things that had gone wrong in his life that formed his character. That was originally the idea. He was gonna have scars and stitches. I have a lot of physical pain, so that was gonna be worked into it. But it was too negative—too dark. I’m trying to be more affirmative. It still has a moodiness to it, but I’m trying not to be too maudlin.”

To view Géza Brunow’s work, visit gezabrunow.com or follow him on Instagram @gezabrunow.

Leave a comment